I avoided the books of Alan Garner as a child. A 1970s Armada Lion edition copy of Elidor sat on my shelf, always taunting me. It might have been the threat of Tolkien-esque high fantasy suggested by its cover that put me off, or maybe, just maybe the sense of dread that permeated its pages were seeping into my world. Now fifty years after it was first published I have built up the courage to enter the world of Elidor.

Set away from Alan Garner’s beloved landscape of Alderley Edge, the action for the most part takes place in 1960s Manchester, an urban environment at a moment of great change. Garner is repelled by cities, but has a grim fascination with the effect they have on us. He sees their impermanence and uses the spell of security that bricks and mortar have over us to create a memorable urban fantasy scenario.

Garner has called Elidor the ‘anti-Narnia’. He met both Lewis and Tolkien during his brief time at Oxford and it’s often assumed that he continued their work. In fact he was trying to do something very different; cutting ties with the high fantasy of Narnia and Middle Earth he brought the folk tales and legends that were part of his own life and history into our world. That impulse is played out strikingly in Elidor.

He rejects the idea of complete escape into the heavenly realms of Narnia possibly because he’d actually visited his own parallel world, whilst spending weeks looking at the ceiling during a childhood illness. And he knew this wasn’t a place he wanted to return. Writing about the land above in his book of essays The Voice That Thunders he says ‘I lived in the ceiling. It was natural, for me… There was no wind, no climate, no heat, no cold, no time… everything was white. I met people I knew, including my parents, and some who were only of the ceiling. The people I knew in both states of waking had no knowledge of the ceiling when I asked them. I soon stopped asking.’

Entering the ravaged land of Elidor through a half demolished Manchester church four siblings embark on an enormously tense quest for four holy items which must be kept safe. The children return to their world unable to face up to what has happened to them. Like the young Garner they soon stop talking about the other place, burying their treasures deep, both metaphorically and physically, in a big hole in the garden.

Roland, the youngest, has a reputation for being a little oversensitive and emerges in the Lucy role, the one who still believes and drives the adventure to its conclusion. But the effect on the other children is just as interesting – Garner explores what might be the effect of such a bizarre experience on these young minds. Nicholas, the eldest, buries himself in psychoanalysis and effects the belief that Elidor is a mass delusion – and ends up approaching some sort of breakdown. The tension between the siblings spills over into an awful lot of arguments, and it’s here that Garner proves himself as a great writer of social realism, with some really stinging dialogue.

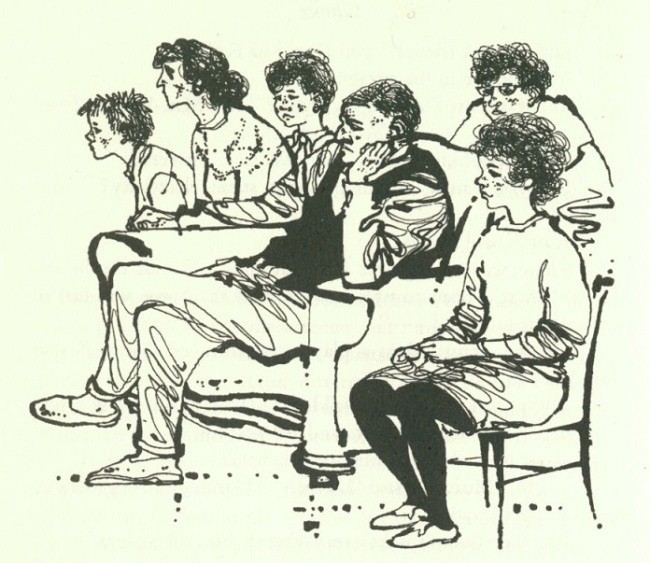

But there is no denying that something tangible is happening. In one particularly memorable chapter the evil forces attempting to retrieve the four treasures make themselves known by interfering with the electrical equipment in the house. This scene takes the book out of the timeless fantasy narratives of his Oxford forebears – and places it firmly in the white heat of the 60s. Unfortunately new technology doesn’t mix with epic clashes between good and evil. When the family sit down for an evening watching ‘the circus; then a play; and then ice skating’ the telly howls and rolls unbearably, while dad’s electric razor and mum’s food mixer take on a life of their own.

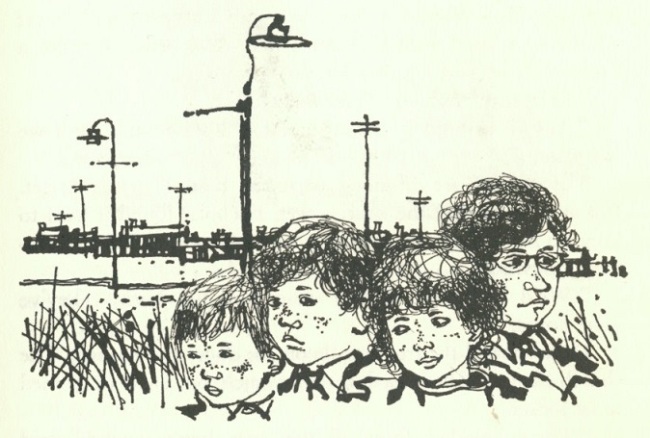

Garner was inspired to write the story after he visited the slum clearances in Salford with the photographer Roger Hill. In the shadow of a ruined church they saw children playing in the remains of back to back houses that are being demolished to make way for Modernist dream homes. Out of the rubble Garner crafts a piece of landscape writing every bit as striking as anything from Alderley Edge. The slum clearances have moved families like Roland’s out of the city centre and into a new suburban landscape. Garner uses the lack of community that they find in this neighbourhood to great dramatic effect. Like J.G. Ballard he sees the horror that is implicit in this anonymous world and uses it to sinister effect.

As the forces of evil close in they find no help from their new neighbours. ‘Visitors were leaving one house, but they stepped back, and shut the door. On the other side of the dimpled glass a broken pattern of a man reached up to slide the bolt… Christmas trees in front windows disappeared as the curtains swirled across.’ This passage was a breakthrough for Garner, ‘the moment of realising that it is a very savage world.’ he wrote.

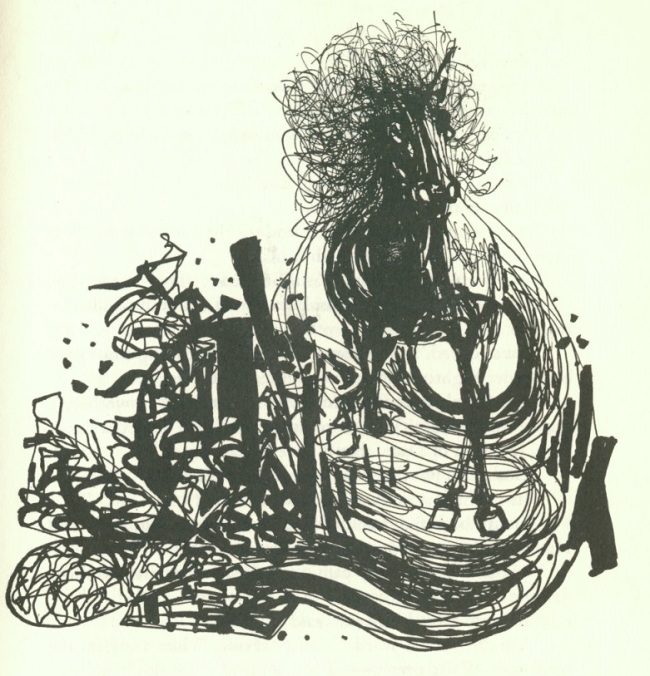

Charles Keeping was hired to provide illustrations, the only one of Garner’s original stories to contain pictures. It’s an inspired choice, the artist was best known at this point for his work on Rosemary Sutcliffe’s historical novels – and he combines his talent for the epic with something altogether more abstract.

The Oxford Companion to Children’s Lit. says Keeping was ‘never entirely content to provide conventional visual material for novels – he argued that it is a fallacy to suppose that a particular incident in the story can be successfully “illustrated”; he believed instead that an artist should capture mood and emotion.’

The last line of Elidor (SPOILERS) plays out Garner’s ‘anti-Narnia’ perspective. ‘The children were alone with the broken windows of a slum,’ he writes. Unlike the Pevensie children who ultimately move into their fantasy world, there is no going back to Elidor for Roland and his siblings. They’ve had a glimpse of paradise, and must now accept their place amongst the ruins of their own world.

Buy Elidor from Bookshop.org

This is such an insightful look at Elidor, reminding me it’s time to revisit Garner’s book of essays, particularly in preparation for a review of Boneland, his completion of the Alderley Edge trilogy. Thanks too for placing this earlier novel in context.

LikeLike

Am working my way up to Boneland – little bit wary of the later books, but sure it’ll be worth the effort. Thanks for reblogging btw.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on calmgrove and commented:

An insightful view of one of Garner’s lesser known standalone fantasies.

LikeLike

Elidor was one of my favourite books as a child, and this was an interesting article….brought up points I never consciously thought about when young….I should reread it all these years later! ‘Green Isle of the shadow of the Stars’ or some such…why do I still remember that, nearly five decades on?

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. Think Garner’s writing is amazingly timeless. Will last as long as the landscapes he describes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you are right!

LikeLike

I think this was too savage for me as a child. Need to have another look at it. Those illustrations are brilliant.

LikeLike

Yes savage is the word. I do wonder sometimes whether these are really children’s books at all?

LikeLike

Enjoyed your analysis, though on one small point I don’t think Roland and co ever lived anywhere near an inner-city slum – he says at the beginning that he lives on “Fog Lane, Manchester 20”, which is in Didsbury, one of the posh bits of Manchester, and I assume they’re moving out to one of the suburbs in Cheshire. They’re middle-class kids who go to look at what turns out to be the demolition of the slum because they’ve gone into the city centre for the day and got bored.

With hindsight, I’m most intrigued by David, the middle brother, who’s neither a denier not a believer but tries to work out the truth scientifically. I wish he’d been fleshed out a little more – and Helen given more to do than be the maid who is makeless.

LikeLike

Thanks for that, you’re absolutely right Harriet. It’s a fascinating portrait of the British class system in the 60s – and mirrors my own family history. Get the sense that they are a working class family attempting to ‘work their way’ into the middle classes. You’re dead right too about Helen – though I think he more that makes up for it in the characterisation of Alison in the Owl Service. Of which more here soon…

LikeLike

If they start off in Fog Lane (a few minutes’ walk from my birthplace), I think they’re middle-class already – if he’d been aiming for working class, I think they’d be in one of the terraces like Whitechapel Street behind the shops on Wilmslow Road, or the little side-streets off School Lane. Fog Lane’s not the poshest, but it’s some way up the ladder, so I’d say they’re probably working their way up through the middle class.

Agree about Alison, and look forward to your comments on The Owl Service!

LikeLike

I bow to your superior local knowledge Harriet!

LikeLike

This sounds brilliant; I shall certainly give it a read. Thanks for introducing me to it!

LikeLike

A really good find for reblogging. The Garner book again illustrates (supported by Keeping’s brilliant illustrations) how deep and thought-provoking novels in the ‘fantasy’ genre can be.

LikeLike

Great piece. Haven’t read this book since I was 10 or so, but remember it being dark and troubling. I’ve just listened to the Radio 4 version but it seemed very sketchy and didn’t really convey what had stayed with me from the book. I’ll have to read it again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read Elidor as a child, following from The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and Moon of Gomrath. I hated the end – not because of the children being stuck in England again, but because of how Elidor was saved. I’ve read it numerous times over the years, and it’s wonderfully atmospheric (and Charles Keeping’s illustrations are brilliant, as ever) but I can’t say it’s a favourite book or even close. I was tricked by the same edition cover you show, but if I’d known what happens at the end, I’d never have read it. I’ve learned to look at the end of potentially appealing books since then …

LikeLiked by 1 person