Throughout his life Alan Garner has drawn on the landscape and legends of Alderley Edge, the place that has been home to his family for many, many generations. It has become more than just a dramatic backdrop though, its hills, rivers and most of all its stones have become the defining character of his writing, providing a link throughout his stories, and a connection with the deep history of the area.

Nowhere is this more vividly felt than when he takes us underground. Below Alderley Edge is a network of caves and tunnels, carved out by men over many hundreds of years as they mined for galen, cobalt and malachite. This underworld was the home to the sleeping warriors of Garner’s first novel the Weirdstone of Brisingamen. And it is here that his young heroes Colin and Susan find themselves in the book’s remarkable subterranean chase sequence.

‘These caverns were remarkable The walls curved upwards to form roofs high as a cathedral, and the distance between the walls was often so great that, at the centre of a cave, the children could imagine themselves to be trudging along a sandy beach on a windless and starless night.’

Garner’s early work is often compared to Tolkein but this is pure Jules Verne. Cast adrift in an alien terrain Colin and Susan are running blind from their unseen perusers. When all appears hopeless though they discover their assumed enemies are in fact allies, the cave dwelling dwarves Fenodyree and Durathror.With their help they are led away through little known passages that prove even more terrifying than a full on assault from the a gathering goblin horde. As Durathror explains to Colin it is the caves that should really frighten them.

‘Mortally I will pit my wits and sword against all odds, and take joy in it. But that is not courage. Courage is fear mastered, and in battle I am not afraid. here though, the enemy has no guile to be countered, no substance to be cast down. Victory or defeat mean nothing to it. Whether we win or lose affects us alone. It challenges us by its presence, and the real conflict is fought within ourselves. And so I am afraid, and I know not courage.’

The claustrophobia that engulfs them as they squeeze through ever tighter tunnels literally takes the breath away.

‘They lay full length, walls, floor, and roof fitting them like a second skin. Their heads were turned to one side for in any other position the roof pressed their mouths into the sand and they could not breathe. The only way to advance was with fingertips and to push with the toes, since it was impossible to flex their legs at all, and any bending of the elbows threatened to jam the arms helplessly under the body.’

Then they approach a hairpin bend and it gets a lot worse for Colin. ‘His heels jammed against the roof: he could move neither up nor down and the rock lip dug into his shins until he cried out with the pain. But he could not move.’ I still get a tightness in the chest reading this piece of sustained claustrophobic brilliance.

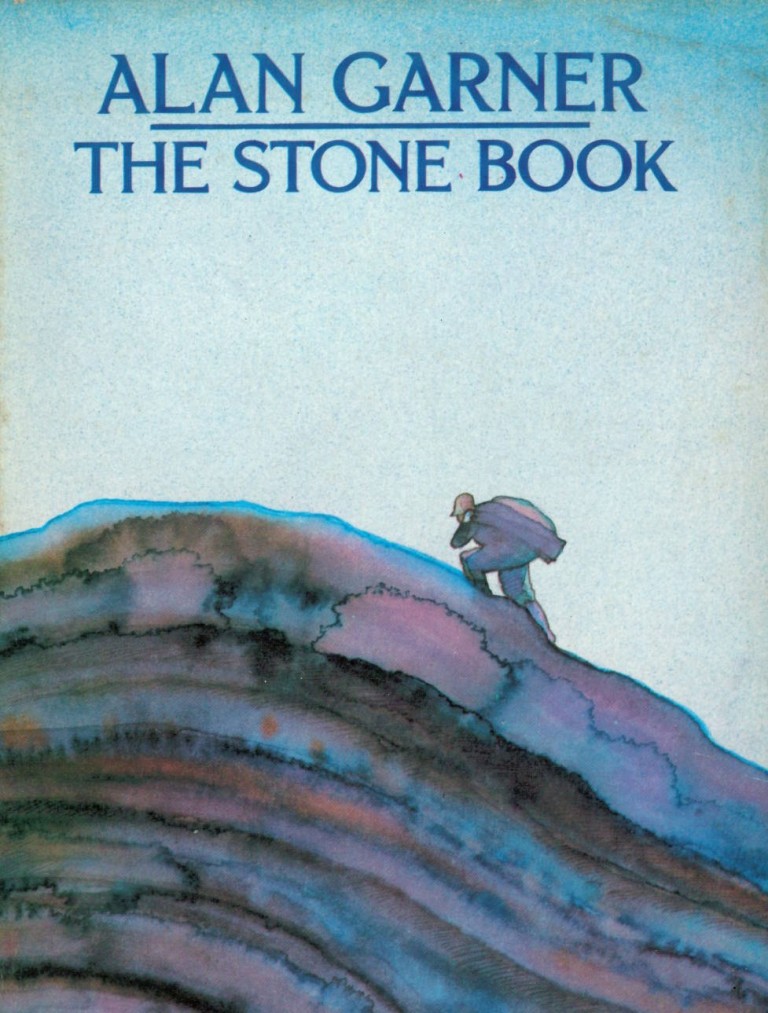

In 1976 Garner returned to the caves of Alderley in the first of his Stone Book Sequence, a fictionalised account of several generations of his own family (you can read about the final part here). We begin in the 1860s, following Mary and her father in a rites of passage under the ‘Engine Vein’, a deep crevice in the rocks, opened by generations of miners.

Like Colin and Susan she must find her own way through the most hazardous part of the cave system. And Gretel like, she unwinds a reel of ribbon, a fragile connection to her father who is too big to go too deep.

‘Mary stood back, in the middle of the Tough Tom, and listened to the silence. It was the most secret place she had ever seen. A bull drawn for secrets. A mark and a hand alone with the bull in the dark that nobody knew. She looked down. And when she looked down she shouted. She wasn’t alone. The Tough Tom was crowded. All about her in the small place under the hill that led nowhere were footprints.’

As well as the ancient cave painting of a bull, she finds a handprint and hundreds of footprints all as fresh as the ones she has just made. In this moment it is as if hundreds, possibly thousands of years of the ghosts of the Garner family are gathered in one place.

‘They were the footprints of people, bare and shod. There were boots and shoes and clogs, heels, toes, shallow ones and deep ones, clear and sharp as if made altogether, trampling each other, hundreds pressed into the clay where only a dozen could stand. Mary was in a crowd that could never have been, thronging, as real as she was. Her feet made prints no fresher than theirs.’

The co-existence of the past and present and the elasticity of time is a central theme in Garner’s writing. The rocks provide a physical and spiritual connection, one that he returns to again and again. His own family history as shown in the Stone Book and the fantastical one of the Weirdstone of Brisingamen are explicitly linked in Garner’s most recent novel Boneland (the final part of the Weirdstone trilogy) when an ice age man carves a bull and makes a hand-print in the rock.

‘He cut the veil from the rock, the hooves clattered the bellowing waters below him in the dark. The lamp brought the moon from the blade the bull from the rock. The ice rang. He took life in his mouth, spat red over his hand on the cave wall. The bull roared. Around, above him, the trample of the beasts answered, the stags, the hinds, the horses, the bulls, and the trace of old dreams.’

In the present day we meet the grown up Colin, haunted by his sister’s disappearance after the events of the Moon of Gomrath, and thoroughly fearful of caves. ‘Black. Shining. Ink – No! Not ink! Water! Black shining water! A river! I can’t swim! I’ll drown! A cave! No! Shining! Shining sky! Stars! No! Galaxies! I see galaxies! More! More than – More! I see! I see! Wonders!’

Colin spends his days looking at the stars, scouring the Pleiades cluster in search of his sister and his nights walking the hills around Alderley like a scholarly wizard desperate for the sleeping warrior to rise from his cave. (SPOILERS) But it is in the rock that he finally meets her, or at least a silhouette of her, not a quite a ghost, but like something carved out of the fabric of the rock by the ice age man, a black hole Susan. And here in the cave Colin finally comes to terms with his loss and his place within the landscape and history. It is a hugely cathartic end to this difficult book, and one that connects the reader ever more closely with the landscape of Alan Garner.

Images taken from The Stone Book, illustrated by Michael Foreman

I read “Weirdstone” as a child – it had particular resonance for us, as Alderley Edge was reasonably local, and a place we’d go on summer days out. The local legends (a particular sinkhole you couldn’t circle three times, lest the devil emerge, for example) added to the uncanny feeling of the landscape.

I’ve not come across the other books mentioned – I’ll have to look them out.

LikeLike

Really, really want to visit. Am going to read Weirdstone with the children first though. I definitely recommend the Stone Book – it’s quite beautiful. Boneland will probably make most sense if you read his other adult novels, Red Shift and Thursbitch, which it is much closer to than Weirdstone.

LikeLike

Thanks for the recommendations – if you do visit, nearby Congleton Edge used to be a nice spot too (although I think there’s been more development around it since I last visited) albeit less steeped in legend.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on enemymindcontrol.

LikeLike

I enjoyed this, these were the exact same editions of the books that I grew up with.

LikeLike

Thanks – they are definitely the most attractive editions. The modern versions are a bit generic fantasy.

LikeLiked by 1 person