‘There’s so much to see and smell here! Whole levels of the library that nobody has been into for a hundred thousand years! Locked rooms full of ancient secrets. Treasure! Knowledge! Fun‘ Garth Nix’s Lirael.

When Birmingham’s new mega library opened last week I was blown away by the sheer scale and heartened by a gleaming symbol of knowledge and learning appearing during these dark days for the public library. A building that is designed to offer immediate access to as much of the library’s vast collection as possible is of course to be applauded. But then I thought about some of my favourite fantastical libraries, housed in labyrinthine old buildings where finding the book you want can turn into a life threatening adventure.

As Michael Rosen explained in his recent Radio 4 series, our library system hasn’t always been quite so inclusive. Many of the world’s first libraries were designed to house private collections as a means of showing how learned you were and showing off your blingy bound volumes. This tradition continued into Victorian times, and I was put in mind of perhaps the ultimate private library, belonging to Sepulchrave, Earl of Gormenghast in the first book in Mervyn Peake’s trilogy.

‘The long shelves surrounded them, tier upon tier, circumscribing their world with a wall of other worlds imprisoned, yet breathing amongst the network of a million commas, semicolons, full stops, hyphens and every other sort of printed symbol.’

The Earl’s collection of a hundred thousand books plays a pivotal role in the story. Housed in a tower in the east wing of the rambling castle it contains all the knowledge of the traditions and rituals of his domain and fills Sepulchrave’s every spare moment. But his absorption in books makes him aloof and unaware there is a cuckoo in his enormous nest. Steerpike ultimately sets the library on fire with the entire royal family inside, the flames ironically are the only thing capable of bringing the library to life, if only for a few deadly minutes.

‘(The Flame) shot forth again and climbed the crimson spiral, curling from left to right as it licked its way across the gilded and studded spines of Sepulchrave’s volumes. This time it did not die away, but gripped the leather with its myriad flickering tentacles while the names of the books shone out in ephemeral glory. They were never forgotten by Fuschia, those first few vivid tiles that seemed to be advertising their own deaths.’

The first real public libraries were first introduced in Britain in the 1850s, but it took a while before people were trusted to actually take the books away. They were either chained up, or had to be ordered through the gatekeepers behind the counter. Simon Eliot, author of the History of the Book described to Michael Rosen how the coming of ‘open’ libraries after WW1 brought concerns that the spread of information could promote corruption, theft and even disease amongst the lower orders. Editions would even contain notices warning borrowers not to return books if they had any communicable disease.

It’s an idea that still pervades fantasy fiction like Harry Potter, where library books can be life threatening and the librarians are there to keep you from the really juicy stuff in the restricted sections. In reality it’s the keyboards that are the health hazards and the librarian has evolved into a very different beast, as Neil Gaiman commented on the Culture Show recently, ‘We have spent hundreds of years training a breed of human trained to go out, find information and come back with it.’

China Miéville takes the idea of the highly evolved librarian and runs with it. In UnLunDun he creates a Wonderland style ‘Bookladder’, a vertical library many miles high that connects our world and the alternate reality of UnLondon. So treacherous are the conditions in the bookladder that it takes highly trained ‘extreme librarians’ or ‘Bookaneers’ to retrieve your order. They’re a proud, daring and obsessive bunch:

‘There are risks. Hunters, animals and accidents. Ropes that snap… Twenty years ago I was in a group looking for a book someone had requested… After weeks of searching, we ran out of food and had to turn back. No one likes it when we fail, so none of us was feeling great. We felt that much worse when we realised we’d lost Ptolemy. Some people say he went off deliberately. That he couldn’t bear not to find the book. That he’s still out there in the Wordhoard abyss, living off shelf monkeys, looking. And that he’ll be back one day, book in hand.’

There’s an even cooler ‘bookladder’ style library over in the Old Kingdom, dug out of a glacier by a bunch of learned magicians called the Clayr. It’s the workplace of Lirael, the eponymous heroine in the second book of Garth Nix’s Abhorsen series.

‘The library was shaped like a nautilus shell, a continuous tunnel that wound down into the mountain in an ever-tightening spiral. This main spiral was an enormously long twisting ramp that took you from the high reaches of the mountain down past the level of the valley floor several thousand feet below. Off the main spiral there were countless other corridors, rooms, halls and strange chambers.’

The library of the Clayr is permeated with learned magic in the form of charter marks, visual symbols that link together to make a spell. The books pulsate with these marks – like the burning volumes in Sepulchrave’s library. And in the depths, behind magic marked doors lie rooms filled with great trees, lakes and dangerous free magic wielded by creatures like the terrifying Stilken, a praying mantis type creature, ‘generally taking the shape of a comely woman.’

The free magic combines with the charter magic to create one of my favourite ever talking animals (a fairly short list). The disreputable dog – or the disreputable bitch ‘if you want to get technical’ – is like a canine Cheshire cat, elusive, playful and not entirely trustworthy. She stalks the corridors, unnoticed, going to the toilet in dark corners and sneaking into peoples bedrooms, making the library fun and exciting. A little like the audio books section in the real world.

Perhaps the most fantastic library of all though, and perhaps the one that Ed Vaizey should visit, is the one where young Matilda Wormwood unlocks her remarkable reading abilities.

‘The books transported her into new worlds and introduced her to amazing people who lived exciting lives. She went on olden-day sailing ships with Joseph Conrad. She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and to India with Rudyard Kipling.’

Though Mr Vaizey probably shouldn’t go on a Monday, Wednesday or Saturday afternoon, as he’ll find the library shut. And as for wonderful Mrs Phelps, the librarian who first spots Matilda’s talent, unfortunately she’s been replaced by a machine and a group of rotating pensioners who, despite their good will, aren’t really trained librarians at all, and would most likely steer a lone five year old girl away from the Dickens and back to the delights of Biff, Chip and Kipper. Or perhaps social services.

The most fantastic libraries it turns out are about much, much more than books.

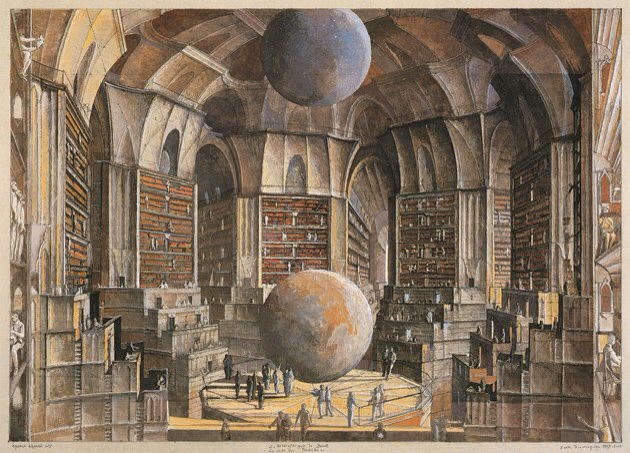

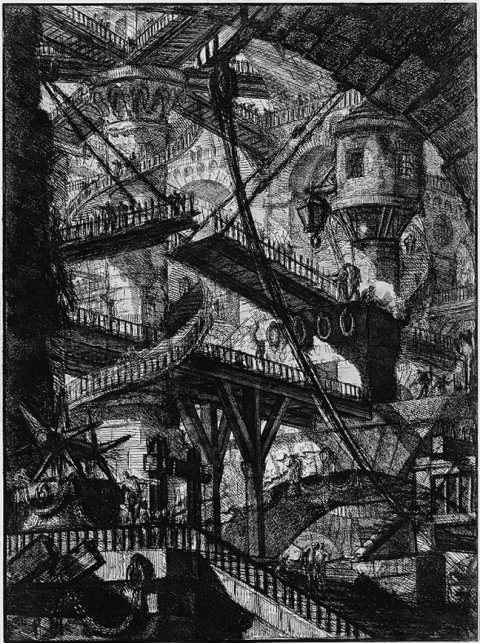

Most of the pictures in this piece are taken from Jorge Luis Borges’s The Library of Babel, illustrated by Érik Desmazières.

What a wonderful selection of images – GORGEOUS!

LikeLike