R is for Russia

‘Let me teach a child for four years and the seed I’d have sewn could never be destroyed.’ So said Lenin shortly after the revolution of 1917. From the start the intention was to mould young minds to become model Communist citizens. Enthusiastically taking up the challenge were a group of artists following Kasimir Malevich, who in the years leading up to the revolution had created Suprematism, a new form of abstract, anti-art. It was with this intent that they approached children’s books.

El Lissitzky, a contemporary of both Malevich and Chagall, was one of the first to respond to Lenin’s call, writing and illustrating the Communist Manifesto of children’s literature About Two Squares.

In the years following the revolution El Lissitzky turned away from painting altogether and concentrated on a new type of graphic art that took avant garde experiments in typography and design straight to the people.

In About Two Squares we are introduced to a black square, representing Malevich’s famous artwork of the same name, the painting that had acted as a full stop in the history of art. Then there is red square, representing the communist movement. Together they crash to earth from outer space, and reorganise the chaotic mess they find in their own image.

Published in 1922 this was to be the starting pistol for a flood of remarkable children’s books built around the ideas of Suprematist and Constructivist art. In his essay from the graphic history of revolutionary Russian children’s books, Inside the Rainbow, Arkady Ippolitov writes ‘Soviet children’s book design of the 1920s and 1930s is the acme of all design before and after… books in which an absolute balance between message and image has been found.’

This vibrant new literary art form, along with the graphic design and poster work that now defines the era is all the more remarkable for having been born out of official state mechanisms. Soon officially sanctioned schools of writers and illustrators sprung up, offering a home (and steady work) for some of the era’s great artists.

Their collective goal was laid out by the children’s writer L. Kormchy in Pravda: ‘In the great arsenal used by the bourgeoisie to fight against Socialism, children’s books occupied a prominent role. In choosing our cannons and weapons, we have overlooked those that spread poison. We must seize this ammunition from the enemy hands.’

The answer was radical in every sense. Arkady Ippolitov writes ‘The revolutionary avant garde swept away all the lace pantaloons and jabots, and the language became simpler, brighter, sharper, cleaner. There has never been anything like Soviet children’s books anywhere in the world nor could there have been.’ Cheaply produced, using lithographic printing techniques, these eyecatching books turned the head of Noel Carrington. He approached Allen Lane of Penguin books with a British series for children using the same methods. And so Puffin books was born.

Philip Pullman is a fan of children’s books from this era, talking on Radio 4’s Open Book he revels in the artwork which looked to the wonders of the modern world for inspiration. ‘They join in with the enthusiasm for the world of electrification, of machines and trams and they depict them with a joy that’s really infectious.’

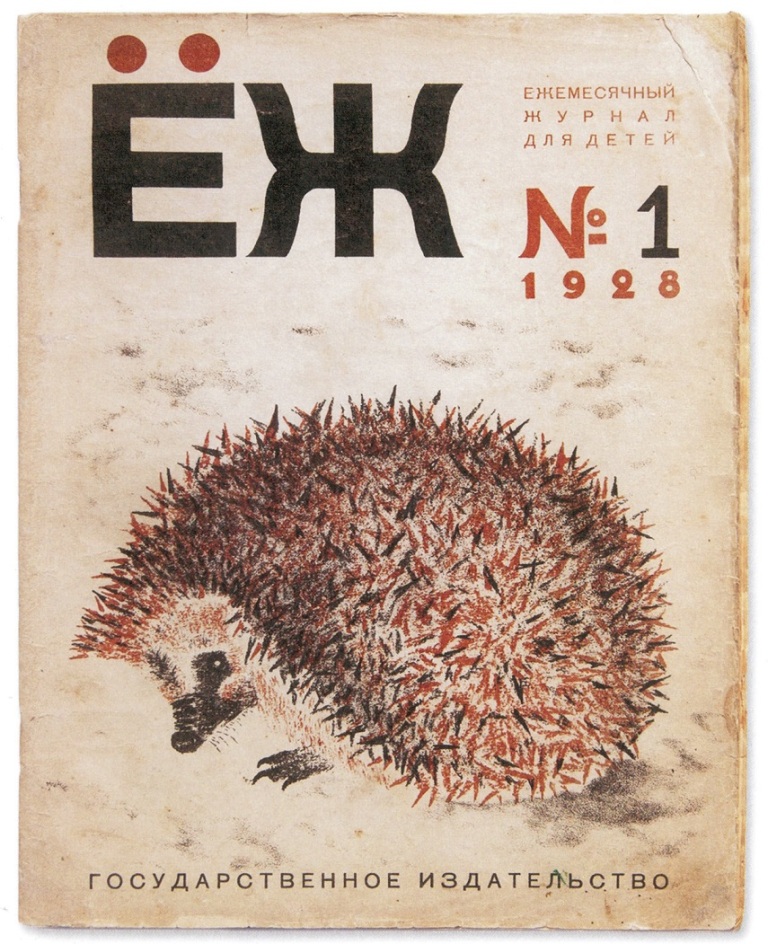

‘It’s not all geometrical and primary colours. Some of the textures are beautifully rendered and almost palpable: Was there ever a pricklier hedgehog than the one peering around suspiciously on page 182?’ Philip Pullman’s foreword to Inside the Rainbow.

‘And the leopard on page 165 looks as if it comes fresh from the brush of Brian Wildsmith.’

The closest western comparison that Pullman can draw from the same era is between Boris Ermolenko’s catalogue of work wear, Special Clothing (1930) and Eric Ravilious’s High Street from 1938. The textures and colours might be similar, ‘but what a world of difference in the social context!’

Now take Osip Mandelstam and Boris Ender’s Two Trams and compare it with that other tale of troublesome machinery, Rev. W. Awdrey’s Three Railway Engines.

Both books come laden with messages about fitting in to their respective societies, but where Awdrey’s steam powered story requires its readers to buy in to a century old moral code (and its visual trappings), the tale of Two Trams wears its purpose lightly and looks like it’s arrived from the distant future.

The subtitle of El Lisitzky’s About Two Squares, ‘To all, for all children’ was sadly far from the reality. Revolution, civil war and famine left the country with between 4.5 and 7 million orphaned and homeless children (that’s one in three children). They remained outside the bold ‘imaginationland’ offered by this new literature and most ended up dying in prisons or camps following Stalin’s decree banning homelessness.

Many of the era’s artists and writers (including Osip Mandelstam, author of Two Trams) would also face the same fate, their radical ideas no longer fitting in to Stalin’s idea of ‘socialist realism’.

‘But for a few years Russian children’s books were free of the darkness that descended over the Soviet Union, and the light they shed, a lovely primary-coloured geometrical wonderland-light sparkling with every conceivable kind of with and brilliance and fantasy and fun, is here in this book still.’ Philip Pullman.

Inside the Rainbow – Russian Children’s Literature 1920-35: Beautiful Books Terrible Times is published by Redstone Press.