Roald Dahl used to talk with some pride about what he called his ‘child power’. He couldn’t move objects with his mind like Matilda or wave a vengeful magic finger, no. What he believed he could do, according to biographer Jeremy Treglown, was ‘walk into any house in Europe or the USA and if there were children living there, be recognised and made welcome.’ Not the sort of claim people make so much these days, but it was true, I was one of those children. Wielding his walking cane Dahl would have seen off Adam Ant, E.T., even Spider-Man in the queue to my front door.

By the 1980s Roald Dahl had (mostly) given up trying to be an Important Adult Writer and was instead positioning himself as a Classic Children’s Author (‘The World’s No. 1 Storyteller’, as he is billed today). In a letter to his editor Stephen Roxburgh, Dahl refused to remove some particularly English references from the Witches for the benefit of American readers. This, he believed, would be akin to rewriting Alice in Wonderland.

Dahl became a great advocate of children’s books, regularly arguing for their cultural value and claiming that they were much harder to write than books for adults. But he had faced criticism from adults throughout his career, and after previous controversies about his portrayal of ethnic characters, in the 80s turned on his treatment of women. Ultimately none of this hurt him, ‘I don’t give a bugger what grown-ups think about it,’ he told Roxburgh. Child Power™ made him unstoppable.

Dahl now spoke to his audience more directly than he ever had before. During interviews he explained that he could remember exactly what it felt like to be very young, and he made the experience of the child more central to his work.

The 1980s began with the Twits. Dahl reveled in his disgusting lead characters and plotted a most terrible comeuppance. The narrative is simply a series of increasingly twisted tricks designed to appeal to kids in the playground. Glass eyes in beer glasses, frogs in the bed, worms in spaghetti, furniture on the ceiling. Dirty, outrageous and lacking any kind of improving qualities the Twits was pure punk and I loved it.

George’s Marvellous Medicine followed in 1981 and was criticised for being even more irresponsible, a young poisoner’s handbook encouraging children to play with harmful household materials.

George is playing a game familiar to all children – mixing stuff together to make an outrageous, smelly mess. The carpet in our house is stained with many such successful experiments.

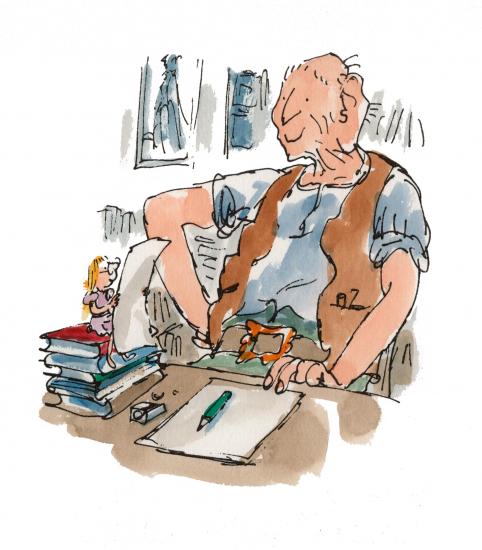

In a shift from his previous work, most of Dahl’s best stories from this period feature a domestic setting, or at least somewhere very familiar to a young audience. Here Quentin Blake’s illustrations show us the world from George’s point of view. Compared to him everything is over-sized – the saucepan is massive, the shelves out of reach. Blake of course is the other key ingredient in Dahl’s revitalised work, providing a lighthearted counterpoint to the writer’s misanthropy.

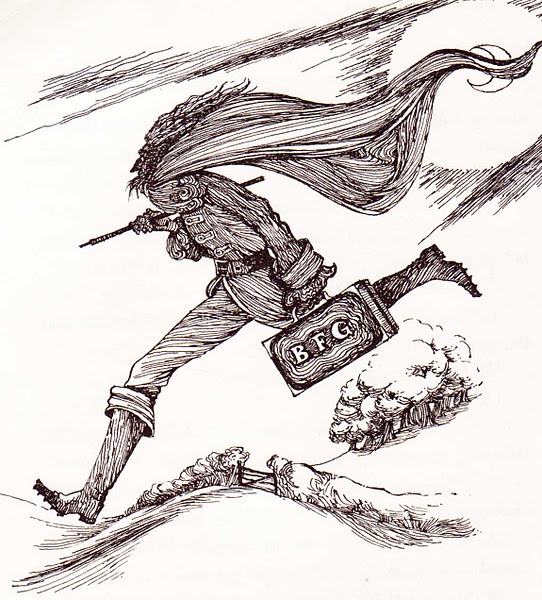

Dahl’s first grandchild Sophie was born in 1977, a relationship that allowed Roald to play to his strengths as a real life big friendly giant, and which was famously immortalised in the BFG (1982). Interestingly he chose to return to the character who first seen in Danny the Champion of the World, the subject of a bedtime story told by father to son. Dahl himself fills many roles, storyteller, hero and now loving grandfather.

For a book that deals with such enormous characters, Dahl is careful to keep Sophie at the centre of things, and this is what makes the book work. The threat to her becomes very real, and the magic tangible. Plus, you know, farting.

The Witches (1983) looked for inspiration to the darkest corners of the Norwegian folklore and Dahl’s own family history, most obviously his close relationship his own Grandmother.

Erica Jong (one of those Important Adult Writers) called it ‘a love story – the story of a little boy who loves his grandmother so utterly (and she him) … It is a curious sort of tale but an honest one, which deals with matters of crucial importance to children: smallness, the existence of evil in the world, mourning, separation, death.’

The original draft contained two chapters full of autobiographical details from Dahl’s time at school. This was cut and ended up as the basis for his next book, the memoir ‘Boy’ (1884) with its memorable tale of a trick played with a dead rodent in a sweetie jar.

Matilda (1988) Dahl is often celebrated as one of his most humane stories, with its cast of angelic teachers and unfortunate children at the mercy of the terrible Trunchbull. But Matilda herself, defined by her love of books, is never over sentimentalised. In fact in the original draft Dahl cast her as a practical joker who is ‘born wicked’ and comes to the aid, not of Miss Honey, but Miss Hayes, a lady with a gambling problem, which Matilda puts right by fixing a horse race with her magic eyes.

The final draft makes Matilda’s victims are far more deserving of their fate. Her tricks are among Dahl’s most memorable. Some, like the ghostly parrot up the chimney are great farce, while others like the superglue on the hat all too easy to imitate.

By the end of the decade Dahl was physically exhausted by ill health. His Child Power faded, the final reserves of magic were diverted into stories about adults cleverly disguised as children’s books. But he had done enough. The fantastic stories he wrote in the ’80s ran the gamut of childhood experiences and cemented his place in children’s literary Valhalla.