‘Fictional food’s not reliable,’ says Alexei, a character from Katherine Rundell’s third children’s novel The Wolf Wilder. This incorrect assertion is something Rundell disproves again and again in her delicious books.

‘I think food grounds a story: gives realism to the maddest plot, gives breathing space to the wildest action, brings comfort and humanity to any book. It evokes the real world even as it surpasses it.’

Read Alice in Wonderland and the stories of E Nesbit, through Enid Blyton, Roald Dahl and practically any great children’s writer and you will find descriptions of food a thousand of times better that in could ever taste in real life. One of Katherine’s favourites examples is Joan Aiken’s the Wolves of Willoughby Chase, and it’s description of porridge with near magical properties. Writing in the introduction to the Folio edition of the book she says:

‘It is easier to trust a writer who writes great food. They are a person who has paid attention to the world… of rooting your world via the senses and galvanising the imagination by evoking real-life hunger. Joan Aiken writes some of the best food in the business.’

So that’s breakfast sorted, but which fictional characters would Katherine invite to dinner and what courses would they provide?

‘For an appetiser, I’d ask William Brown to bring liquorice water, as a kind of cold soup; not because I think it would be very satisfying but because I’ve wanted all my life to know what it is.’

‘For the main course I would have Bilbo Baggins provide a breakfast-as-dinner.’

‘And for dessert, Willy Wonka, who could bring a light selection from the factory. I think they’d get on.’

Food serves a variety of different purposes in Katherine’s books. A connection to the animal world in the Wolf Wilder, of giddy excitement in Rooftoppers and in the Girl Savage food starts as a playful part of her main character Will’s life in rural Southern Africa.

‘Will had had to bake her food in open fires, or in the hollows of the tree roots, which was nicer anyway; she made meals that tasted enticingly of smoke and leaves, and eggs and animal, and Africa.’

The Girl Savage’s Mint Chocolate Bananas

Split open the banana skins with shards of sharp flint. Sprinkle salt and pepper on to the green ones, use a single wet finger to poke brown sugar into the yellow. Crush two large squares of mint chocolate and sprinkle into the bananas. Wrap in foil and bravely place the bananas deep into the papery embers of the fire. Now for the best bit – wait with your chin on your knees while the bananas make promising noises. A fat luscious feeling.

How much of this was based on her own experience growing up in Zimbabwe?

‘All of it! The bananas baked in a fire, the fruit eaten straight from the tree, the mopane worms – all of it is real, and from my own childhood.’

But as Will moves away to England, food becomes a strange and serious business and Will remembers a saying from back home: ‘Life isn’t all mangoes and milktarts.’ A wonderful phrase which I will be using, and which has introduced me to an amazing new southern African pudding.

I asked Katherine what her secret was.

‘I try to cook every piece of food that goes into the books. I think food is such a good way to inject the real into the imaginary that it’s worth making it as true as possible. I think the recipe for tomato soup in Rooftoppers actually makes a fairly delicious meal.’

Rooftoppers’ Tomato Soup

Take a pile of large flattish tomatoes (enough to reach to an eleven year old girl’s knee), the sort with a swinging kick to the taste are best. Tip all the tomatoes except two into brass cauldron shaped pot and add a cup of rainwater (you can use tap water in times of drought). Over the next half-hour, as you wait for the tomatoes boil down into a pulp, eat the spare pair raw. Check the cauldron occasionally and fish out any skins that float to the surface with a twig or your fingers. Don’t discard the skins – they make a perfect snack for roosting pigeons. Take a quick sip of the cream then tip in most of the jar. Season with some salt and a little pepper cracked between two scraps of slate. The soup should now smell so rich it makes your nose shiver. Pour into a tin can and sit with you back to the wind then laugh.

However there are a few dishes she hasn’t tried. ‘I draw the line at the roasted rats in Rooftoppers and the spitted jackdaw in The Wolf Wilder.’

Wolf Wilder’s Spitted Jackdaw

Find a spot where the snow is thin and tear down some branches for firewood. As the fire stutters to life, halve and gut a jackdaw. Don’t waste time plucking the bird, instead slice the skin off and throw the scraps to the wolves. Cut one half of the bird into slices and hold these on sticks in the flickering tips of the flames. Place the other half, still in a lump, into the burning heart of the fire. When the lump turns black take it out and chew forty times, or until your jaw mutinies, then spit out into the snow. By now the meat from the top of the flames should be cooked. Pull it off the stick with your teeth so a little blood and juice oozes down your chin. It should taste magnificent, like a bolder kind of pigeon.

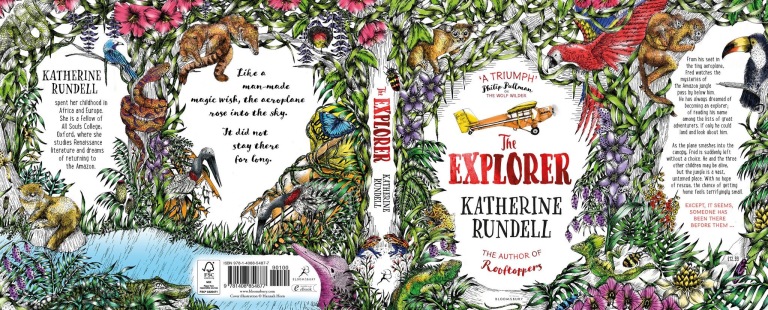

Katherine Rundell’s fourth book, the Explorer lands in August. Can we expect more inspiring foody scenes from the heart of the Amazon? ‘I hope they’ll be memorable! I loved writing them. I don’t want to give too much away but, in a word: tarantulas.’